In E.G. Ballard's 1914 book,

Cap Streeter Pioneer (page from book at left), Streeter tells his entire life's story in his own words. Excerpts from the chapter "Battles on the Lake Front" detail the ongoing developments of his proclaimed "District of Lake Michigan":

Streeter in his own words:

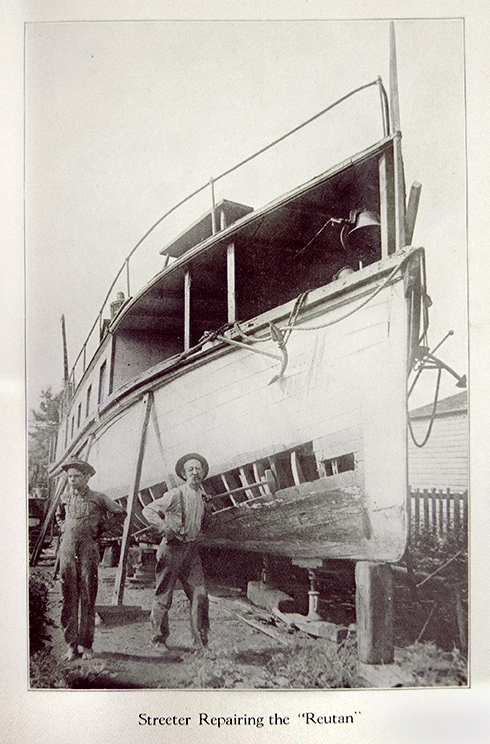

I had met an old friend, Captain Bowen, who had spent many years in Honduras, and during that time had ingratiated himself with the government of that country, securing large concessions of land and a commission in the army of that new republic. He advised me that the government very much desired to have regular steamboats plying on certain of its rivers, and that if I would build a boat for that purpose and navigate the same in accordance with their desires that I could secure a very large grant of valuable land and ample compensation for my services, and at the same time build up a lucrative business. The plan was very attractive, and during the winter and spring of 1886 I built a steamboat, which I christened the “Reutan” late in that spring. I determined to try the steamer out on Lake Michigan first, and fitted her out for passenger traffic, making regular trips to Milwaukee and other local ports every day for several weeks.

On the 10th day of July, 1886, I took a private party to Milwaukee, and during the trip the lake became exceedingly rough and stormy; in fact, so much so that the party decided not to risk the return trip, and we endeavored to return to Chicago alone. By the time we reached Racine we encountered a terrific storm which did not abate its fury for many hours, and by that time the “Reutan” was a badly damaged wreck lying on a sandbar off Chicago harbor, behind the government breakwater on the north shore.

It was about ten o’clock at night when we drifted near the breakwater, and just at this juncture the engine broke and became useless. We were then at the mercy of the wind and waves, helplessly drifting about. Fortunately, or unfortunately, just as you may choose to judge by subsequent events, the wind drove us behind the breakwater, narrowly missing a collision with the pier. …

The boat finally stranded in a shallow body of water when 451 feet from the shore. This was at three o’clock in the morning of the following day… I was the only man on deck. My wife and the crew were driven to the berths for safety, and I tied a strong rope about my waist and resolved to witness from the decks whatever happened. Twice I was swept overboard… the waves soon dashed in every door of the cabins, and swept through the boat from end to end, and from side to side. The steamer was flooded.

… The furniture, chairs and sofas were piled up against one end of the cabin by the force of the waves sweeping through the inside of the vessel. Finally the boat was pounded so hard on the sandy bottom of the lake that the bottom of the boat was rent, and the seams of the hull opened up. After this it soon filled with water and sand and sank to the bottom, which fortunately was close at hand, for the hull was about twelve inches above the water line after the sea had subsided, and the bulwarks were about two feet above….

Investigation proved that it would be impossible to pull the boat off this sandy bar with a tug, and that she was too badly damaged in her frame and bottom to float. I decided that this location was to be my home, and I have never revoked that decision from that day to this. … I buckled down to the work very shortly thereafter. I discovered that sand had drifted and banked up considerably, considering the space of time that had elapsed, behind the boat, that is between the boat and the shore. I concluded that I would build up a rock wall on the sea side of the boat and thus aid the deposit.

I then entered into contract with several excavators and contractors who had refuse stone and brick which they wished to dispose of, and they brought hundreds of loads of these materials to the shore at the point nearest to the vessel, and I there reloaded them into the yawl and took them out and dropped them around the boat. By the end of November I had raised a bulwark about the vessel which had caused sand to fill in entirely beneath it so that I could put jackscrews under it and gradually lift it above the water. During this process I was also filling sand beneath the boat as I lifted it up inch by inch…. The boat was now three feet above the water, and I already had a small island constructed by my own efforts, which island was long to be my home…

It was a novel sight, however, during that first winter… it was indeed a natural curiosity, and friends and strangers often came down to us across the ice to see if we could really survive such an experience. The police came frequently to see us during the first winter, and were far ore welcome visitors than they afterward became, as you will readily understand by and by.

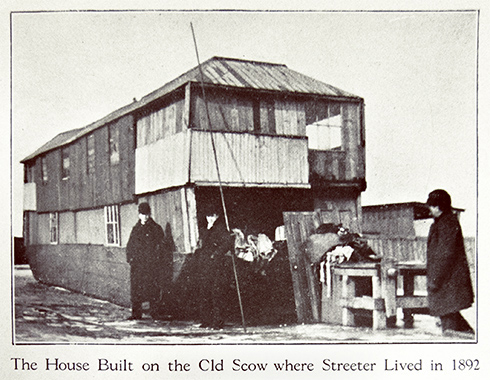

This boat remained our home until the spring of 1893, by which time I had thoroughly repaired and relaunched her, and rechristened her as well. This time I named her after my wife, “The Maria.”… After this relaunching of the vessel our home for some time was on an old scow upon which I had built a two-story cabin, all of which stood upon the ground I had in the meantime constructed and built up from the bottom of the lake until it stood high and dry above water…

At the time of the relaunching of the vessel I had filled in all of the space between my boat and the shore to the west and south, and much farther to the northward, as well as more than thirty rods to the east and northeast. This was a territory of 186 acres, long known to everybody in Chicago as “Streeterville” and as the “District of Lake Michigan,” the latter name having been given to the tract by myself, the former by the people of Chicago and vicinity because of my creation, occupation an ownership of it….

At the time I stranded, building operations on a grand scale were in operation in all parts of the city which had been devastated by the great fire some years previous, and by this condition I was especially favored. Excavators and contractors were very desirous of obtaining dumping grounds as near as possible to their work for all superfluous earth, rock, brick, and refuse which were o no use to them. My filling operations were particularly inviting to them, and I had no difficulty in making contracts with them by which I received millions of loads of refuse and earth with which to fill in the territory about my island home…

After I had virtually completed my filling-in operations as related, I had the tract surveyed and platted, and it was at this juncture that I learned of the displeasure of a lot of millionaires who imagined that the time was ripe to engineer a conspiracy to rob me of my hard earned property…

At the time I was stranded, the location of some of the homes of the millionaire colony of the North Shore were not particularly valuable, nor even desirable for residence purposed. The entire frontage for rods back from the shore was low and swampy, and the location of the present palace or castle of the Palmer family was familiarly known as the “stink pond,” because of the universal use of the pond there to throw garbage and dead animals into, and the odoriferous notoriety of the location as a natural consequence. All this was later filled in, but it was for many years an undesirable locality.

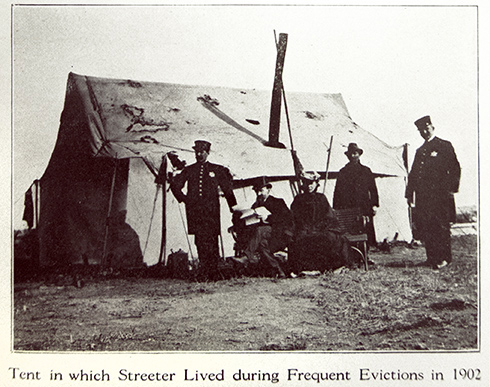

When the millionaires came to realize that I was indeed a landowner they immediately set actively to work to form a conspiracy to rob me of my possessions by fair means or foul; and, as you will perceive, their efforts were confined principally to the latter. If they ever made a truly lawful move I never heard of it, and certainly none of them had any vestige of claim which was worthy of the least legal consideration to a particle of land I had built up form the sea…