1967: The original Museum of Contemporary Art building, featuring Zolton Kemeny's 8-foot tall, 50-foot long bronze relief. Courtesy of the MCA Library & Archive |

|

The area around this Ontario Street location was known as "Gallery Row," and in 1967 featured nearly 15 art galleries, making it an ideal site for the new contemporary art museum. After the MCA leased the building at 237 E. Ontario Street at the end of 1966, the trustees hired the architectural firm of Brenner Danforth Rockwell to redesign the 1908 brick structure that was originaly built as a wholesale bakery plant. For its most recent 30 years, photography studios and then the offices of Playboy Clubs International occupied the open span interior. All three architects, Daniel Brenner, George Danforth, and Harry Phillips Davis Rockwell had studied with Ludwig Mies ven der Rohe who was a proponent of the International Style of architecture. Buildings of that style are identifiable by their rectangular forms, flat roofs and unadorned facades. Brenner Danforth Rockwell covered over the building's six windows, resurfaced its brickwork with stucco, and faced the building's surface with a 50-foot-long bronze relief that contributed to the structure's finished form and design. Inside, the exhibition spaces featured movable partitions and fabric-covered walls. An additional feature of the MCA's complete design was a moat filled with anthracite coal. In an October 26, 1967 Chicago Tribune article titled, "Coal Dumped for Art's Sake," Alven Nagelberg reported, "The Museum of Contemporary Art, 237 E. Ontario St. not only is Chicago's newest haven for way out art, but also the city's only building with a coal field in its moat." Explaining that the moat would protect the bronze relief, Daniel Brenner offered, "We wanted to keep people from touching the sculpture and discourage vandalism, so we created a moat. In medieval days moats were filled with water and frogs and gunk but we didn't think that was practical." He added that their preference was to use polished black pepples, but they were more expensive and he thought people would take the stones. At the museum's opening, the entrance fee was established at 50 cents, and 25 cents for children under 16 and students. In 1969, fares doubled to 1 dollar, and 50 cents. In January 1969, as part of his exhibition, "Wrap In Wrap Out," the Bulgarian artist, Christo, created his first North American wrapped building by covering the outside of the MCA in brown canvas and the inside of the museum in white canvas. See a recent Chicago Public Radio story, accompanied by photographs and a short film shot by the MCA's first curator David Katzive, here. In December 1969, Tribune columnist Eleanor Page reported that the MCA had soldout its December 18th Women's Board store's gala opening party. A Women's Board's representative described the store as "something like an upright refrig freezer, on rollers which opens out to an eight foot width. It stands six feet tall. It is black formica inside and out." Page suggested to her readers, "If you're already the proud possessor of a $12.50 ticket for the 18th, wear your mod clothes, and make them colorful, too. And if you don't have your ticket, get in line for a repeat party in February for the opening of the Lichtenstein exhibit." |

|

1980: Museum of Contemporary Art after the acquisition and adaptation of the 235 E. Ontario Street building. Photo: Tom Van Eynde, courtesy of the MCA Chicago Library & Archives |

|

In less than ten years, the Museum of Contemporary Art's needs changed. Initially intended to operate as a Kunsthalle - an art center that displays, rather than collects art works - some early donations initiated a small collection that soon signaled a shift in the museum's mission. Additionally, by the mid-1970s, the original building seemed inadequate and dated. Upon the 1979 completion of the new building, New York Times art critic, Hilton Kramer, wrote: "When the museum first opened in 1967, its façade was dominated by a 50-foot metal relief designed by Zoltan Kemeny, the Swiss artist – a work of questionable taste that has been removed." After a quest for a new or additional space, in 1976 the museum acquired the adjacent townhouse and expanded westward. The three-story brownstone stood on a 20x100 foot lot and according to a February 10, 1976 Tribune article by Alan Artner, it was occupied by a "beauty parlor, interior design firm, food laboratory, and basement cocktail lounge." A February 1976 MCA press release stated that the new acquisition "is a forward step in a planned expansion program and coincides with the establishment of a permanent collection of modern works of art." The MCA's announcement continued: "The additional space will help to accommodate a growing permanent collection, active exhibition schedule, ambitious programming of theater, music, dance, film, poetry and symposia and will provide as well for additional staff and preparation areas." In January 1978, Gordon Matta-Clark, an artist known for cutting into buildings to reveal their structure and history, then photographing the results from strategic viewpoints, created a work from the MCA's newly acquired brownstone building. Called Circus or The Caribbean Orange, it would be Matta-Clark's last work before he died of cancer at the age of 35 later that year. See photographs of the process and resulting work, here. See information about the MCA's recent exhibition related to this project, here. |

|

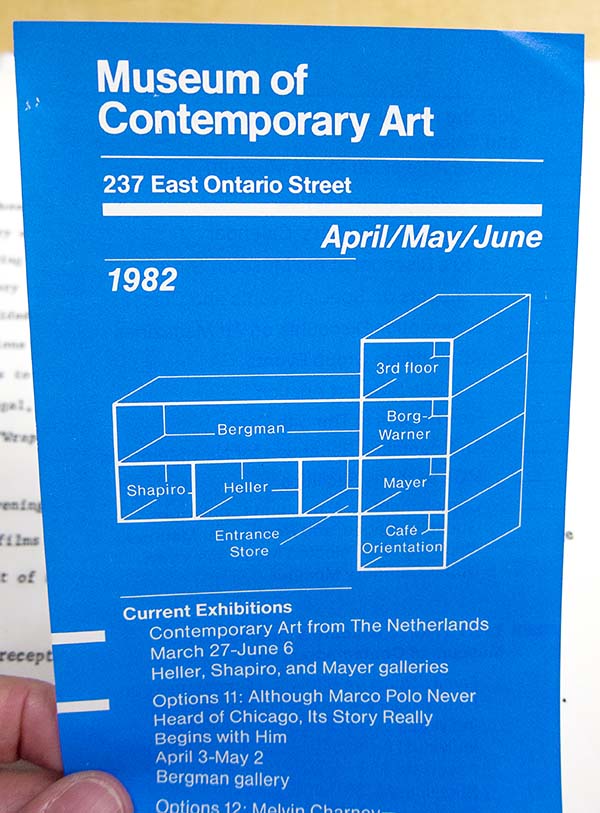

Exhibition brochure presented courtesy of the MCA Library & Archive. |

The MCA chose Laurence Booth of the architectural firm, Booth, Nagle & Hartray, to redesign and connect the two buildings; the museum stayed open during nearly three years of construction. At the new museum's completion in March 1979, Chicago Tribune's architecture critic, Paul Gapp proclaimed, "The expanded, renovated, and enhanced Museum of Contemporary Art is an architectural success." Gapp described the building's surface: "The facade of the structure is clad with burnished aluminum, a favorite material of many modern sculptors. When viewed obliquely, it reflects the north light in rainbow hues. Granite is used as facing and paving on the front entrance deck." The New York Times' Hilton Kramer also praised the new building: "For the new façade, Mr. Booth has given the building a more “open” look. There are a second-floor gallery visible from the street and an attractive combination staircase and ramp at the entrance graced by an open-work neo-Art Deco metal railing that has a good deal of delicate sculptural presence in its own right." The 1982 exhibition brochure at the left illustrates the gallery layout of the 1979 museum. The Borg-Warner Corporation had donated money to fund a gallery for Chicago artists within the museum. In 1979, working with the building's architect, sound artist Max Neuhaus imbedded a 30-speaker sound piece into the walls of the west stairwell. At the end of 1981, coinciding with his museum exhibition, Charles Simonds converted 44-feet of brick wall space to into a miniature cliff dwelling villiage; the basement cafe became The Site Cafe. When the MCA later outgrew this building, they left Simond's and Neuhaus' work behind. Five years after opening ceremonies, and at a time when the surrounding galleries had moved westward, the MCA announced that they had outgrown their Ontario Street building and they were looking for a new enlarged space. In 1978, while 237 E. Ontario was under construction, Governor James Thompson had announced that the state would be selling the armory and moving the Illinois National Guard to a new location. In July 1984, MCA officials expressed interest in the armory site four blocks away from their newly renovated building. On November 30, 1993, a ceremonial groundbreaking established the MCA on Block 21. The new museum opened at 220 E. Chicago Avenue in June 1996 - 30 years after the original trustees pursued their idea of a contemporary art museum. |