On April 18, 1970, the Chicago Tribune reported that Jan Van der Marck had resigned as the museum's director, having given notice at that week's board meeting. Regarding the reason for his departure, Van der Marck shrugged,

"Nothing in particular, I thought it was time to recharge batteries. The museum is no longer an infant, things are in fairly good shape, and April 15 seemed a fitting ceremonial date."

Jan Van der Marck left the MCA in July 1970. David Katzive, the museum's first curator, assumed the directorship until a replacement could be found. Katzive resigned in October and on October 31 it was announced that Mario Amaya, chief curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Canada would be appointed the MCA's new director.

October 31, 1970

On December 2, 1970, the MCA held a press conference to introduce their new director. Described in the Tribune as a 37-year old Brooklyn-born bachelor, Amaya shied away from questions regarding any plans he might have until he met with the exhibitions committee later that day. With equal conviction as Van der Marck's reasoning for leaving the MCA, Amaya said that he decided to accept the position because,

"the city seems to be going thru an exciting period of social and political change. I want to be part of the action, I guess."

On January 21, 1971, the MCA announced that Mario Amaya decided that he would remain at his position of chief curator in Toronto.

The search ended at the end of March when Stephen Prokopoff, the director of Philadelphia's Institute of Contemporary Art agreed to take the job.

Joseph Shapiro assumed the role of museum director during the Van der Marck and Prokopoff gap.

February 27, 1974

At the end of February 1974, 69-year-old Joseph Shapiro resigned his position as president of the board of trustees, stating to the Tribune's Alan Artner ,

"Now is the time when the museum needs younger and more energetic leadership." Artner's article concluded,

"No indication was given as to who the candidate might be, the rumors have centered around Edwin A. Bergman, the 33-year-old president of Chicago's U.S. Reduction Company."

May 4, 1974

July 10, 1974

In July 1974, Ira Licht signed on as the MCA's new curator, replacing Patricia Stewart who resigned in May. Stewart had stepped into the position in October 1971 after David Katzive assumed the role of acting-director in 1970.

Beginning in 1970, and continuing through 2009, Alan G. Artner covered the art scene at the Chicago Tribune. During his forty year tenure, he wrote boldly about his impressions of the Chicago art world and its exhibitions.

His chronicles of the early years, especially, provide some behind the scenes commentary. Similarly, from the 1990s through the early 2000s, Chicago's free weekly,

The Reader, reported on the MCA's organizational changes.

April 20, 1974

Edwin A. Bergman assumed the role of president of the board from 1974 until Lewis Manilow replaced him two years later. Alan Artner reported,

"Manilow is one of the museum's founding fathers, has served as the first chairman of the Exhibition Committee, and heads the Committee on the Permanent Collection."

During this period - from 1974 through 1976 - museum growth and evolving philosophies that resulted in accepting art donations, complicated what first sounded like a simpler idea of an alternative art center. Trustees began a quest for a bigger museum space as donations established a permanent collection.

In a longer article, focusing on Lewis Manilow's new role, Artner puts the first public face on the museum's behind-the-scenes business:

"Last week Manilow was elected president of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and if ever an institution could use his powers of organization, this is it. Ever since the museum's founding in 1967, some members of the art community have felt that it has been run by a limited circle, an ingroup with well-defined tastes. Because the organizational structure remained small, it has been unkindly called a "family museum."

Regarding the issues surrounding organizational disarray, Lewis Manilow stated bluntly,

"Joe Shapiro founded the museum. Joe ran it. Joe built that house, and because he did and was the kind of person who really 'lived' there, most of the rest of the people tended to stand back a little. He did everything, and had it not been that way, it might not have been at all."

Alan Artner's article also brought up issues that I encountered during my

conversation with former MCA director Kevin Consey regarding the roles of the curatorial staff and trustees in exhibition choices:

"Though Manilow believes that "exhibitions are primarily the staff's responsibility" and does not want to risk infringement, he promises that there will be a look at all the past shows to see what's been left out. He wants a balance: venturesome exhibitions, also popular ones; retrospectives of modern masters; shows involving local artists."

July 31, 1977

On July 31, 1977, under the title,

"MCA's Prokopoff ends his stable but static reign," Alan Artner wrote that Stephen Prokopoff's

"abrupt departure puts the MCA into an extremely difficult position." And in a scenario that would repeat itself over the next decades, he continued:

"In a little more than a year, the museum has changed its president, curator, administrator, and director of education. That this is happening on the eve of the museum's 10th anniversary, midway through plans for expansion and the enlargement of a permanent collection, does not exactly build confidence." Curator Ira Licht had resigned in April 1976.

In elaborating on the article's title, Alan Artner offered that Stephen Prokopoff directed the museum stealthily, avoiding any conflicts or daring moves. Then, revealing a backstory, Artner stated,

"Supporters might be disappointed by the financial opportunities missed. Members might be puzzled over the repeated postponement of major exhibitions. The artistic community might even complain about aloofness or lack of interest. But little of this seemed to matter - at least not to the museum trustees."

Chicago Daily News art critic Dennis Adrian was also sympathetic to Prokopoff. In his July 23, 1977 article,

"A musem man's lot is not so hot," Adrian stated,

"Money is not the only problem, but it is the trigger for many others. Museums are obliged to depend upon increasing public funds, either federal or local. As this happens, how (if at all) do their responsibilities change toward the public, the community or artists and scholars, collectors and others?"

Adrian continued,

"Do cultural centers and similar organizations take over the educational functions into which, a few years ago, museums were so anxious to throw themselves? Is it a responsibility of museums to acquire, if possible, the holdings of important area collections so that such works remain locally as artistic resources for all?

Many of these questions fall upon artistic directors in museums. Trustees cannot as a rule have the necessary background in the now gigantic field of American concern with the arts.

This has made directorial jobs nightmarish even in small institutions because of the dearth of qualified support staff (even if there are funds for their salaries). The museum director has to be a one-man band, and have limitless patience, energy and tact.

While to some it may sound undemocratic, intensive knowledge in today's art world is a matter of high specialization and unusual combinations of abilities. The director can stimulate and influence the artistic life of his community, and because this can only occur through practices that seem autocratically imposed, his position is delicate."

| ****************************************************** |

Chicago celebrated the MCA's tenth anniversary with Mayor Bilandic's proclamation of

September 1979 as "Museum of Contemporary Art" month. Even though the museum was then without a director, colorful banners hung along Michigan Avenue and the museum hosted a street fair, a lecture series, a 10th anniversary exhibition, and a celebratory ball. By this time, the MCA had also expanded to include the building next door as part of its space.

Membership had grown to 4,700 and the museum had raised nearly $1.5 million in the last year.

October 31, 1977

At the end of October 1977, Alan Artner announced, "John Hallmark Neff, 33, will become the Museum of Contemporary Art's third director, effective next March 1." Neff arrived in the spring of 1978, leaving a curatorship at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Like the previous museum directors, he was schooled as an art historian, having received a Harvard PhD by the age of 30.

Quoted extensively throughout the article, Neff summarized his perception of his new role: "I came to Chicago with the understanding that I was to direct the museum. The trustees were very careful to discuss the difference between being a director and being a curator, and it is not my expectation to curate a great many shows. Instead, my challenge will be to administer this museum. Raising funds, getting our grants in on time, working with the trustees, collectors, and local artists - there are lots of things to do."

After further elaboration on some of the new director's notions of possibilities, Artner concluded:

"Neff's ideas have not yet been discussed with the museum's various committees, and he is inordinately careful to say they are just ideas. But he has a great many of them about artists who make "traditional" objects and a variety of other people whose thinking he admires. If the MCA's first director saw the museum as a laboratory and the second preferred a neutral exhibition space, the third would seem most content with an open forum." Neff assumed his directorship at the museum in March 1978.

A year after John Hallmark Neff's arrival, in March 1979, the MCA's expansion was unveiled. Encompassing the three-story townhouse to its west, the new museum nearly doubled its space by adding another 14,000 square feet. The building would soon prove too small for the museum's vision and growth.

In 1978, newly elected Governor James R.Thompson announced that the state would be selling the Chicago Avenue Armory, initiating what, in several years, would become the MCA's next

visionary goal.

March 30, 1980

Although Alan Artner had submitted a glowing appraisal of the

MCA's new building, a year later, his assessments on the orgainization and its programming decisions did not flatter:

"Everyone interested in contemporary art has been for the MCA from the very start. Its founding in 1967 was a noble enterprise one was bound to support even while watching standards and motives decline. Whenever there was trouble, we were expected to put on a happy face. No one wanted to talk about it; the Art Institute was having trouble enough."

Yet the time has come when protective silence no longer will do. Morale at the MCA is extremely low, and it is no secret. When Vito Acconci recently began an MCA lecture by saying his own retrospective exhibition did not work, he unwittingly expressed an opinion that went far beyond the particular show."

Artner's analysis escalated into a tirade that included his opinion that it was a mistake for the MCA to have begun collecting art. His other points included the museum's lack of foresight in not including an auditorium in their new plan, and receiving too many traveling shows as a result of budgetary issues: "Current problems did not begin with the museum's expansion, though they could have been predicted on opening day. The gallery space had been doubled, giving room for more exhibitions. But what kind of exhibitions, and more important, how good would they be? The museum's operating budget certainly was not being doubled."

Artner continued with criticism of programming, citing a lack contextualization of exhibitions, and extended his displeasure to the museum's exhibition catalogues: "The writing was marked by scholarly obfuscation more than scholarship. And the analytical frameworks were, at times, more elaborate and impenetrable than the subjects being discussed."

***************

As with the practice of contemporary art, it would seem that a continual redefining

of the presentation of contemporary art would lead to eternal growing pains. In a 1978 Wall Street Journal profile of Joseph Shapiro titled, "How an Astute Buyer of Surrealist Paintings Acquired His Bargains," the museum's early champion and founder stated: "I always advise young people to collect the art of their times, but that's difficult these days. So much of what's going on seems to be a laboratory experiment to find a 'cure' for art. I recognize that this is part of the broader revolution of our times, but so much of what's being done is so lacking in focus that I don't see how it can endure. But then again, maybe that's just an old man talking."

***************

May 24, 1981

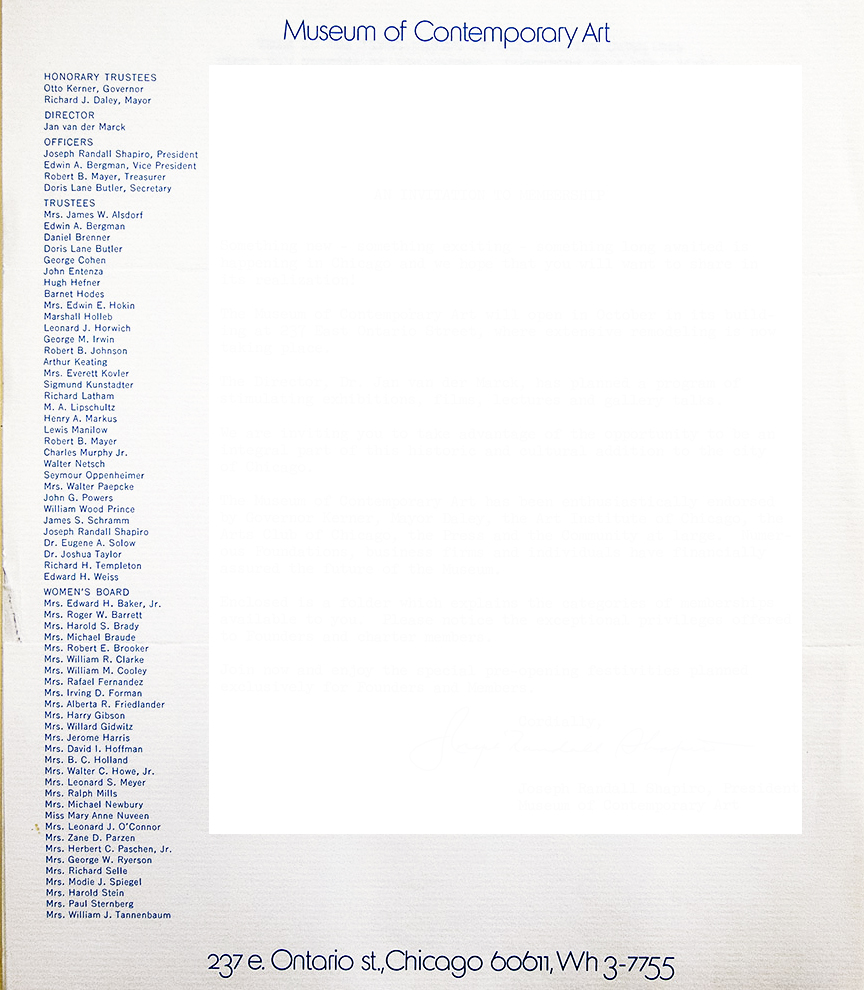

Lewis Manilow's term expired and the trustees elected the MCA's first woman president. Helyn Goldenberg arrived at the helm of the board after already contributing much to the museum's growth: she was a founding member of the women's board (as Mrs. B.C. Holland); was a co-founder of the museum store; and had already served on the board of trustees as its secretary and vice-president, also participating in exhibition, education, and executive committees.

In conversation with Alan Artner, Goldenberg said, "I would love to discuss only esthetics, but the critical issue is financial. Museums are faced with horrible inflation and financial cutbacks from the government. Last year the MCA got government funding that was between 7 and 10 percent of our total income, and we now know it will go down."

"We're going to have to run the museum a little more like a business is run. And even if moneymaking programs never amount to a major part of the budget, they are very important psychologically.

I also have great faith in corporate support of the arts. However, corporations and foundations will have all the same people asking for a lot more money. So we are going to have to rely on the individual. This is something we've always done, and throughout our history the contributions have been huge. But the base has to be broadened."

An ongoing sore point in the MCA's development was its stalled membership enrollment. Membership peaked at around 5,000 and had remained there for a number of years. The museum was getting a reputation of being elite and its exhibitions were not drawing huge crowds.

Helyn Goldenberg was a little unsure of how to remedy the MCA's membership woes: "Over the years we have done a number of things quite well, but membership is not a problem we have solved. You see, none of us really knows whether the potential membership for a contemporary museum in Chicago is 5,000 or 20,000 - we have no frame of reference. If it's 5,000, so be it. But I don't think we have done everything we could do to find that out. Maybe we will have to bring in a consultant, I don't know. But this is definitely an area we have to discuss."

Disregarding the funding and membership issues, but perhaps suggesting a grander solution, Goldenberg stated: "It would be untruthful of me not to say that one of the museum's future plans is to have a larger building. After all, we have grown up and now would know what to do with it. Certainly, we need an auditorium, a place where we can have performances, films, lecture. It has been pretty hard to organize programs in a plant like ours when we have had exhibitions that took up an increased amount of floor and wall space. We need more exhibition space. And we need more space for the permanent collection. This is particularly important because the permanent collection is growing steadily, and when we can offer a plant where we can really show it, we would attract more works."

October 23, 1983

Two years later, Alan Artner embraced the announcement of John Hallmark Neff's departure to recapitulate his views of the MCA's problems. Re-iterating the "family" aspect of the earliest museum, Artner suggested that the board had a larger

hand in the museum's public face than one would suspect - excerpts:

Although [Neff] says his parting with the MCA is amicable, longtime museum watchers may discern a pattern of hope followed by discontent that has characterized the tenures of each of the three directors in the museum's 16 years.

Professionals, meaning the director and staff, are supposed to be in charge of museum operations. Volunteers, including trustees and affiliate groups, are expected to give support - not least by raising funds. At a small museum, however, proprietary interests often develop. A tight circle of supporters may grow to think of itself as a "family" who is free to determine more than it should.

Sometimes a director will want to bring in people with whom he had worked comfortably before, but because MCA curator Judith Russi Kirshner had the allegiance of several trustees, Neff felt thwarted in replacing her.

The problem that did resurface, as it routinely seems to do at the MCA, was the one involving clear lines of power. Perhaps this could have been predicted, for as the museum's first and second generations of trustees were succeeded by a third, similar degrees of commitment carried similar possibilities for encroachment.

In Artner's several-column feature article, he also divulged some backstory to earlier museum history and summed up the past directorships: "[Neff] followed Stephen Prokopoff, who had been given the choice of ejection or resignation. Prokopoff ran afoul of trustees who perceived him as too mild in relation to the first director, the dynamic Jan Van der Marck. Essentially a caretaker's administration was sufficient for six years, but then a new board president, Lewis Manilow, realized that the MCA really wasn't going anywhere, and Prokopoff left before the movers (and shakers) cleared him out. Neff arrived 5 1/2 years ago as the golden boy who could give the MCA a bright national profile."

Taking his critical assessment of the MCA board up a notch, Artner continued his harangue by rehashing former director choices: "Trustees look longingly to the achievements of Van der Marck, yet his highly vocal assessments of the restrictive conditions under which he worked dampened the possibility of engaging a strongly independent curator. Prokopoff made no show of independence, but then he, too, left, which seemingly added to what Van der Marck had said. The impression was that MCA trustees were unsure about the kind of leadership they wanted. And that was as good as saying they did not know a free hand was something a man of vision naturally would require.

"In fact, vision was seldom mentioned until Neff's last year. Everyone "made nice" in public, then whispered that vision was the quality he lacked. This was supposed to explain the director's alleged shortcomings, but in Neff's case, who is to say that limited vision was not partly attributable to the meddling that limited his power? Vision grows through practice. Power gives practice form."

Alan Artner's provocative essay spurred the public response of former board president, Lewis Manilow, who submitted a seven paragraph clarification of the role of the trustees at the museum - excerpts from his October 30, 1983 letter to the editor:

"Trustees of cultural institutions must advise and support, with overwhelming emphasis on support. They must make policy in many areas, but must be careful not to intrude on aesthetic questions. At the MCA the only constraint the trustees place upon the director is financial, for we cannot survive, much less grow, unless we live within our budget. All exhibitions and acquisitions are determined by the staff. Committee approval is usually required, but almost invariably obtained.

Frankly, I think that the fear the trustees overstep their authority arises not from facts, but from the suspicion that active, energetic and interested trustees (and we are that) might be tempted to be too active. Perhaps such suspicion is even a good thing, since it warns us to be circumspect. But there is potential harm that unfounded suspicions can only hurt an institution we are all proud of.

The MCA will soon hire a new director. As with all previous directors, he or she will be given total responsibility for staff, exhibitions and acquisitions, constrained only by budget. I am confident that this policy will continue to be followed and that the Museum of Contemporary Art will continue to make Chicago proud of it in all respects.

May 17, 1984

Several months after John Hallmark Neff's departure, I. Michael Danoff accepted the job as the MCA's fourth director. Danoff, then director of the Akron Art Museum, would join the museum in September. Board president, Helyn Goldenberg, commented, "Our hopes for the new director were that he would continue to bring the best of contemporary art to Chicago, continue to hone and perfect the museum's permanent collection, expand the educational programs and acquire a more adequate facility to accommodate the other goals. I believe Mike Danoff is the person who will help us carry out those objectives.

For the first time in the museum's history, the director would solely assume

an administrative role; curator Mary Jane Jacobs handled the exhibitions.

***************

In July 1984, the Museum of Contemporary Art expressed interest in the site of the Chicago Avenue Armory, which for the previous six years had been the object of other groups' conversations

surrounding changing times and struggle for prime lakefront real estate.

During the next two years, as strategizing and planning for a new museum site progressed, the MCA's organizational structure remained fairly intact. At the end of 1985, an internal study determined that there was crucial need for a new space and the board initiated fundraising efforts. According to an MCA brochure, in March 1986, Beatrice "Buddy" Mayer, "hosted a dinner party at which nine trustees committed $5 million for a new museum." The following month Governor James Thompson appointed a task force to explore new uses for the armory site, and in January 1987, the task force recommended the land be used for an "art museum and sculpture park."

***************

In 1986, Helyn Goldenberg's 5-year term was up and in September of that year, John D. Cartland became the board of trustees' new president. Cartland, a senior partner at an accounting firm, first set out to balance the museum's budget. Understanding that the MCA would soon start a fundraising campaign for a new museum, he figured that the current state of affairs should promote confidence. Accordingly, he began with cutbacks and conversations around some restructuring. Regarding board/staff expectations, in a conversation with Alan Artner, Cartland emphasized that the staff would "run the museum more totally than probably they've been asked in the past."

Just days before Cartland assumed his new position, after six years at the post, Mary Jane Jacob left her position as the MCA's curator to become the chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Michael Danoff and associate curator Lynne Warren handled exhibition planning for 1987.

***************

The board was already moving towards acquiring the Chicago Avenue Armory site

and in April 1987, museum officials submitted a proposal to Governor Thompson. In December 1987, initiating a creative real estate deal, the R.R. Donnelley factory plant on Chicago's south side was donated to the MCA. More than a year would pass before more progress was made towards the armory site.

***************

August 2, 1987

A new chief curator arrived, and like with other MCA organizational developments, Alan Artner submitted an interview with the incoming official. Bruce Guenther, aware of the MCA battles between trustees and staff, stated: "The museum director has administrative responsibility and also sets an esthetic direction, which therefore may mean involvement in some aspects of acquisitions and exhibitions. The curator is concerned very specifically and primarily with the exhibition program and the development, enhancement and growth of the permanent collection. The trustees determine the institution's philosphy and goals.

Now, it's clear from the conversations I have had that there's a great deal of confusion about that, about whose job is whose. This is true at every museum. But I as a staff member believe that certain things are my responsibility and that I have been hired to perform those functions as a professional in the field.

Our exhibition schedule cannot be determined by trustees' most recent collecting patterns or their most recent conversations with a New York dealer or the whims and enthusiasms of their most recent spouse. In the broader goals of an institution there is a broader vision at work; there must be, in order for an institution to exist and grow, and there is here at the MCA."

Alan Artner's Sunday feature article

also updated the MCA's quest for a new location, mentioning that the armory site was the forerunner.

July 14, 1988

In a move to help alleviate the growing responsibilities of the

the museum director, 32-year-old Mary Ittelson was hired as the MCA's first associate director. In my conversation with Ittelson, she suggested that she came on board with the understanding that a transition to the Chicago Avenue Armory site was a done deal. But, the swap of the R.R. Donnelley buiding for a relocation of the Illinois National Guard would not proceed until May 1989.

August 10, 1988

Within weeks of assuming her new museum role, Mary Ittelson became the MCA's acting-director. Ittelson's background was not in art; she had been a dancer and was a founding member of Northwestern University's dance department. But, she left a job as a managemenet consultant and had a fresh outlook, and within a year of her assuming the leadership of the museum, it had received its largest gift.

April 23, 1989

By 1989, the armory

had been secured, a new business model helped establish institutional roles, and a progressive plan was instituted for funding the museum's new venture. While officials continued their search for a new director, chief curator Bruce Guenther became Mary Ittelson's co-director of the museum. This April newspaper article announced a further division of labor and notice of official re-titling: the president of the board would now be called the "chairman," and a new position of deputy chairman was added. The president of the board had previously also served as chief executive officer, a position that would now be assumed by the museum's director. The article announced that Paul Oliver-Hoffman was the nominee to replace John Cartland at his term's expiration, and that Jerome Stone was the nominee for deputy-chair.

In June, Jerome Stone assumed the role of the Chair of Chicago Contemporary Campaign - a $55 millon dollar capital campaign.

July 24, 1989

In the largest single

grant in its twenty-two year history, in July, 1989, the MCA received a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation of Chicago. The money was earmarked for educational programs in the new museum.

August 27, 1989

After

establishing its new organizational structure, museum officials announced the hiring of a new director. New board chairman Paul Oliver-Hoffman stated, "Kevin Consey represents the new generation of museum directors, combining uncompromising artistic vision with strong management skills, and capital campaign experience. He has acquired a reputation for being one of the most dynamic and visionary young directors in the contemporary art field."

Consey also commented on his appointment: "I'm honored that the museum's board and staff has asked me to be director. I'm very excited about coming to Chicago and look forward to understanding the MCA's challenges." Kevin Consey came to Chicago fresh from the directorship of the Newport Harbor Art Museum in Newport Beach, California, where he had led a $50 millon capital campaign for that museum. Listen to my conversation with Kevin Consey to hear his 24-year removed recollections of his tenure as the museum's president and CEO.

***************

Kevin Consey arrived in Chicago, beginning his directorship in November 1989. The initial amiability between Consey and Paul Oliver-Hoffman, the new chair of the board of trustees would soon waiver.

In 1991, after a two-year chair's term, Oliver-Hoffman stepped down. Although never reported in print during their tenure together at the museum, the friction between the two men ended up affecting the MCA's capital campaign for the new museum. In January 1998, the museum filed suit against Oliver-Hoffman in an attempt to retreive an unrealized pledge of $5,000,000. Playing out in the national press, it was only the second time a museum had sued a donor for non-payment. On January 11, in an article that directly addressed the innuendo between the two men, Alan Artner quoted named sources who confirmed instances of disagreement over museum financial business. In July 1998, the dispute was settled: the Oliver-Hoffman estate would donate two works from their art collection to cover the pledge - a Chuck Close portrait of Cindy Sherman, and "Banner," a 1990 work by Anselm Kiefer. Paul Oliver-Hoffman had passed away in April. Kevin Consey left the museum at the end of May.

***************

From Kevin Consey's arrival in 1989 until the new MCA opened on the Chicago Avenue Armory site in June 1996, the museum's organizational structure remained largely intact. In 1991, Allen M. Turner stepped up to the position of chair of the board of trustees, having served as the museum's treasurer under Paul Oliver-Hoffman.

Turner also chaired the selection committee for the search of an architect for the new museum, and after a one-year search, announced in May 1991 that the committee had chosen Josef Paul Kleihues. Hear my conversation about this process with Allen Turner, here.

On February 28 1991, the MCA announced that former Governor James Thompson had joined the board of trustees for a 3-year term. Instrumental in obtaining the armory site, Thompson's 14 years as Illinois' Governor had concluded when his final term expired in January 1991.

In August 1991, chief curator Bruce Guenther announced his departure from the museum, and in May 1992 he was replaced by Richard Francis, who arrived in August 1992 after ten years at the Tate Gallery in London.

In an heroic achievement, accomplished during 17 months that included the interim between Guenther's departure and Francis' arrival, associate curator, Beryl J. Wright planned and launched the exhibition, Art in the Armory: Occupied Territory. The Tribune's Alan Artner called the show, "one of the largest and most complex projects ever attempted by the Museum of Contemporary Art." The exhibition, which opened in September 1992 was the armory building's swan song; it would be demolished when the exhibition closed.

From the 1993 armory site groundbreaking, until the new MCA opened with a 24-hour summer solstice celebration in June 1996, the Museum of Contemporary Art

continued its programming at 237 East Ontario Street.