Many Illinois Governors have been involved in the transformation of the site explored in this Shifting Grounds project.. Their duties have related to the transition of occupants on Block 21, and as commander-in-chief of the state's military, it has been their responsibiliy to activate the National Guard during emergencies. Governor Richard J. Oglesby was one of the first to travel through the Chicago Lake Tunnel in 1865, and twenty years later, while he served another gubernatorial term, legislation was put forth giving the Lincoln Park Commissioners the power to build Lake Shore Drive on the state's submerged land. In 1915, Governor Edward F. Dunne negotiated the land swap for the original armory building, and in 1917, his successor, Frank O. Lowden attended the ceremonial laying of the new armory's cornerstone. State monies under Governor Henry Horner funded the 1935 addition to the Chicago Avenue Armory, and in 1940, when Horner died in office, his body laid in state within the new builidng. In 1968, Governor Otto Kerner, who joined the Black Horse Troop in 1934, and retired as a major general in the National Guard, accompanied Michael Butler to see Mayor Richard J. Daley about the impending unrest at the Democratic National Convention. Kerner's successor, Governor Samuel H. Shapiro deployed the Illinois National Guard during the 1968 convention's riots. In 1978, less than a year what would be a fourteen-year term as Illinois' Governor, James R. Thompson announced his plans to close two Chicago armories and build a new one in the suburbs. This announcement initiated a fifteen-year journey that eventually led to Thompson agreeing to a land swap that landed the Museum of Contemporary Art on Block 21. |

|

September 14, 1978 From 1978 to 1985, discussions around the armory's future and the National Guard organization waxed and waned. At the initial announcement, Thompson said that the property would sell for the land's fair market value, which at that time was $12 million. The Tribune reported that the property would be first offered to city and state agencies, and if no offers were made within 60 days, the sale would be open to private buyers. The Governor explained that National Guard enlistment was down, and the sale would relieve the state of maintenance costs, as well as a $1.4 million remodeling project. Five days after Governor Thompson's announcement, Chicago Tribune architecture critic, Paul Gapp, weighed in. Suggesting that the city should buy the site, demolish the armory and make the space a public park, he wrote, "This would create a grand and almost uninterrupted corridor of public recreational and breathing space stretching all the way from Michigan Avenue to the lakefront." After describing all existing elements of Block 21, Gapp concluded, "This is the time to make a little plan for a little park that will bring joy to people forever." On October 4, State Senator Dawn Clark Netch wrote to the Tribune's editors commending Paul Gapp's suggestion, and adding, "For two years I have been urging Gen. Phipps, adjutant general of Illinois, to dispose of the Chicago Avenue Armory on the grounds that it is largely unused, an eyesore in a beautiful community, and an irrational use of that great location." Netch continued, "Under no circumstances should it be sold to a private developer for the addition of another 60-70 story high-rise to an area that is already the single most congested part of Chicago." Her missive ended with a reiteration of her plea: "I urge your continued support to make sure that the Armory is closed and that its replacement will add to the beauty, not to the disfigurement of one of Chicago's great assets." |

|

October 11, 1978  Paul Gapp reported back to the Tribune that the group, the Greater North Michigan Avenue Association (GNMAA) supported converting the land to a public park, but also felt that it was possible to keep the building for other public uses. By this time, petitions were circulating condemning the idea of a private sale. The GNMAA committee set its sights on pursuing the possibility of a "reversion clause" on the legislation that turned the city's land over to the state. The group's president added, "We're also exploring recycling the armory, and ideas like putting some big transparent domes on top and turning it into a conservatory or an ice skating rink." |

September 19, 1978  |

March 29, 1979 |

|

Six months after Governor Thompson's announcement of the sale of the armory, the Streeterville Organization of Active Residents (SOAR) group's petition had accumulated 1,500 signatures, demanding that the site not be sold to a private developer. SOAR, along with the Greater North Michigan Avenue Association (GNMAA), insisted that a private developer would construct a high-rise on the parcel. They also feared that Northwestern University would expand its medical school and hospital onto the land. One suggestion, which had come up before, regarded constructing an underground parking facility to finance and maintain the proposed park. |

|

July 13, 1981  More than two years later, no progress has been made regarding selling the armory. In this Chicago Tribune article that addresses some tension between the National Guard and the Streeterville residents, Robert Enstad writes of meeting Col. Faite Mack, the armory's custodian and "military aide to the governor," who says, "There are a bunch of rich widows living over there and some of them have three damn dogs." Mack complains of having to pick up dog waste after the "widows" call downstate to have the park cleaned. The article also tells of other instances that demonstrate the love/hate relationship between the Guard and the neighborhood residents through the years. Enstad acknowledges that the building sale is on hold, and notes that in the previoius month, a bill to authorize the sale was defeated in the Illinois House by one vote. James K. Williams, an assistant to Governor Thompson, said that there was no impending sales timetable, adding that Thompson didn't believe that he needed the House's permission. |

|

October 6, 1982 The photograph that accompanies this headline shows a representative from the Save the Armory Coalition standing alongside Illinois State Representatives Jesse White and Barbara Flynn Currie, while two reporters with long microphones appear to be interviewing them. The occasion of the photograph is a protest of the selling of the armory. |

|

April 21, 1985 Meaningful conversations around the Armory's plight stopped for several years. While I could not find any Tribune stories that reported the Museum of Contemporary Art's intersection with the Armory parcel before April 21, 1985, on January 2, 1985, an angry letter to the Tribune's Editor, under the heading, "Armory gift," begins, "So, Gov. Thompson wants to give the Chicago Avenue Armory to the Museum of Contemporary Art! I'm sure the people at the museum appreciate his generous impulse. There is one thing wrong with the idea - very wrong. The Armory doesn't belong to Gov. Thompson. It belongs to you and me." In this long article by Catherine Collins, which continues on two pages of the Tribune, she outlines the Museum of Contemporary Art's quest to find a new space for their growing museum. Along with an image of the looming eastern entrance to the armory, there is a photograph of a smiling Helyn Goldenberg, chair of the MCA's board of directors, seated before a model of a renovated Chicago Avenue Armory; Michael Danoff, the museum's director, stands over her, also smiling at the architectural model. Collins writes, "An emerging national trend has made strange bedfellows of big business, government and cultural institutions. From New York to Los Angeles, the three have joined forces to save some of the financially struggling institutions or play midwife to many of the new ones." She cites the example of New York's Museum of Modern Art and the soon-to-be Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. The article describes the MCA's intention of renovating the armory building for its purposes. Acknowledging that the armory's 275,000 square-foot space is twice the size that they would need, a partial tear down is mentioned with the intention to maintain the building's basic structure. [The MCA's interior space at this time was 40,000 square feet, with 1,500 square feet of storage space.] John Booth, the architect who designed the recent addition to the MCA's Ontario Street location, worked out some different plans for the armory building and its site. He suggests a scuplture garden for a carved out middle section that would leave the armory's original colonnades intact. Citing MoMA's and LACMA's partnership with corporations to offset costs, Booth and Goldenberg posit different approaches: Booth suggests a 20-story building at the museum's east end; and Goldenberg spoke of "a commercial structure to house all of Chicago's foreign consulates." |

|

April 28, 1985  In this editorial by architecture critic Paul Gapp, he recaps the history of the armory site's plight since he responded in print to Governor Thompson's 1978 announcement that he would be selling the Chicago Avenue Armory. Gapp, compelled to write because of the article, above, about the MCA, reiterates his argument that a park should take the place of the armory, and emphasizes " the need for such a greenway." And yet, he continues, "the MCA has now moved in with a tentative proposal that may be a serious threat partly because it is cloaked in cultural respectability. Its plan has been inspired by museum schemes in other cities." Gapp goes on to suggest that the city should buy the land; the MCA should look elsewhere; or the state should demolish the armory to create a new park. In a June 15, 1985 article titled, Plea: 'Don't give armory to art museum', in the neighborhood newspaper, Near North News, the emphasis is again on demollishing the armory and keeping the ground as an open park space. The unnamed author also mentions creating an underground parking facility and offers that the Chicago Park District has agreed to build and operate the proposed park. Continuing with arguments against the MCA's relocation, the author states: "The Museum of Contemporary Art is now located at 237 E. Ontario. Some neighbors have complained that it is so elitist that most would be art-lovers are denied admission." Also in 1985, 42nd ward alderman Burton Natarus sponsored a down-sizing ordinance that restricted new construction to the armory's current height. Crain's Chicago Business, September 14, 1987 MCA Closes in on Armory, but legal woes loom. This article by Michael Warren begins, "An 11-year battle over the Chicago Avenue Armory may end soon, if a legal tangle over the site's ownership doesn't prolong negotiations." Acknowledging that land values have increased by 50% since the armory's last appraisal in 1981, it was valued at $11-14 million at that time. Warren mentions that the MCA proposed signing a 99-year lease with the state, instead of assuming the land's ownership. Local alderman Burton Natarus raises a compelling question: "The big legal questions is, in light of the fact that the land was originally deeded for the purpose of building an armory, would that property revert back to the original owners if the Armory were razed?" But the answer is that too much time has passed for re-claiming the land. Illustrating political intricacies, Warren writes: "If Mayor Washington goes along with Gov. Thompson's decision to lease the property to the MCA, then the title question might be a mere technicality. But the issue could be a bargaining chip for the mayor in his feud with the governors over leadership of the McCormick Place Board and the proposed White Sox stadium." The issues raised with which governing body owned the rights to the armory parcel echo the history of the building out of Lake Shore Drive. Crain's Chicago Business, September 21, 1987 Armory's happy ending. This short unsigned article begins, "We're glad to see a happy ending in sight to the 11-year battle over the Chicago Avenue Armory site. Gov. James Thompson is about to sign off on a plan to raze the 70-year-old armory, making way for an ideal new home for the Museum of Contemporary Art." See information about the Chicago Avenue Armory's 1987 building appraisal, here. |

|

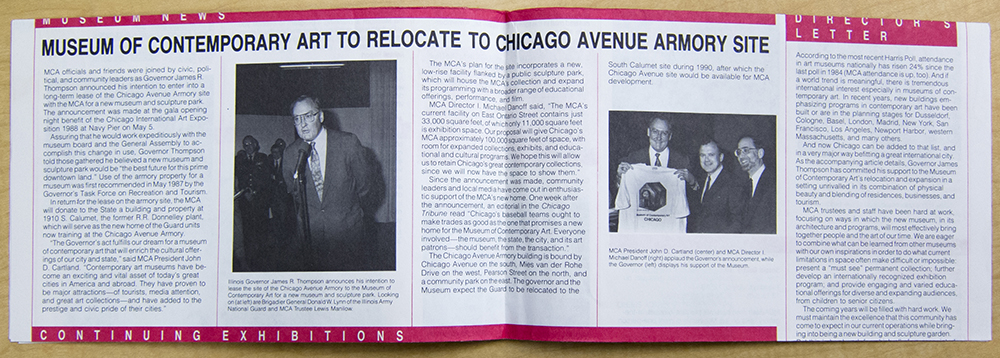

May 6, 1988  This Tribune article by Constanza Montana details the final negotiations that led to the MCA's acquisition of the armory parcel. During the first week of May, 1988, Governor Thompson stated that he approved "a plan whereby the property of the State of Illinois commonly known as the Chicago Avenue armory, will be leased for a period of 99 years to the Museum of Contemporary Art for the purpose of allowing the museum to demolish the armory and construct a new museum." In exchange for the 99 year dollar-a-year lease, the MCA donated a 140,000 square foot building for the National Guard's use as an armory. Governor Thompson was happy with the swap, reasoning that it favored the state because the $3.5 million needed to convert the new building was the same amount as would be necessary to upgrade the Chicago Avenue building; also, he felt that the current operating costs of $250,000 per year would be cut in half with an updated facility. |

May 12, 1988 This short unsigned article begins, "Chicago's baseball teams ought to make trades as good as the one that promises a new home for the Museum of Contemporary Art. Everyone involved - the museum, the state, the city and its art patrons - should benefit from the transaction." |

1988 Museum of Contemporary Art brochure: Courtesy of the MCA Chicago. |

|

| November 30, 1993 Ground breaking ceremony for the Museum of Contemporary Art. Pictured from left to right: Governor James R. Thompson, State Representative Sydney R. Yates, MCA CEO Kevin E. Consey, MCA Architect Josef Paul Kleiheus, MCA Trustee Beatrice Cummings Mayer, NEA Chair Jane Alexander, Chicago First Lady Margaret Daley, MCA Board of Trustees Chair Allen Turner, and MCA Trustee Joseph Shapiro.  Photo: Jim Prinz © MCA Chicago |

|

| After 14 years as Illinois' Governor, James R. Thompson's final term expired in January 1991. On February 28, 1991, Thompson was elected to a three-year term on the MCA's board of trustees. | |