|

Major Milton J. Foreman requested that the 1st Illinois Cavalry of the Illinois National Guard convert to the 2nd Illinois Field Artillery for service in the World War. On July 1, 1917, the 2nd Field Artillery was established, and on July 25, they were called to service and established camp on the Lincoln Park grounds of today's Lake Shore Park. Battery A left at the end of August, and by the beginning of September the entire regiment had gone for training at Houston's Camp Logan. On September 21, the 2nd Field Artillery I.N.G. was converted to the 122nd Field Artillery as part of the 58th Field Artillery Brigade, a unit in the 33rd Infandry Division. On May 26, 1918, the regiment shipped out for France where they stayed in service for nearly a year. For a thorough reporting on the Illinois Regiments' World War I service, see the free e-book, Illinois in the World War.

|

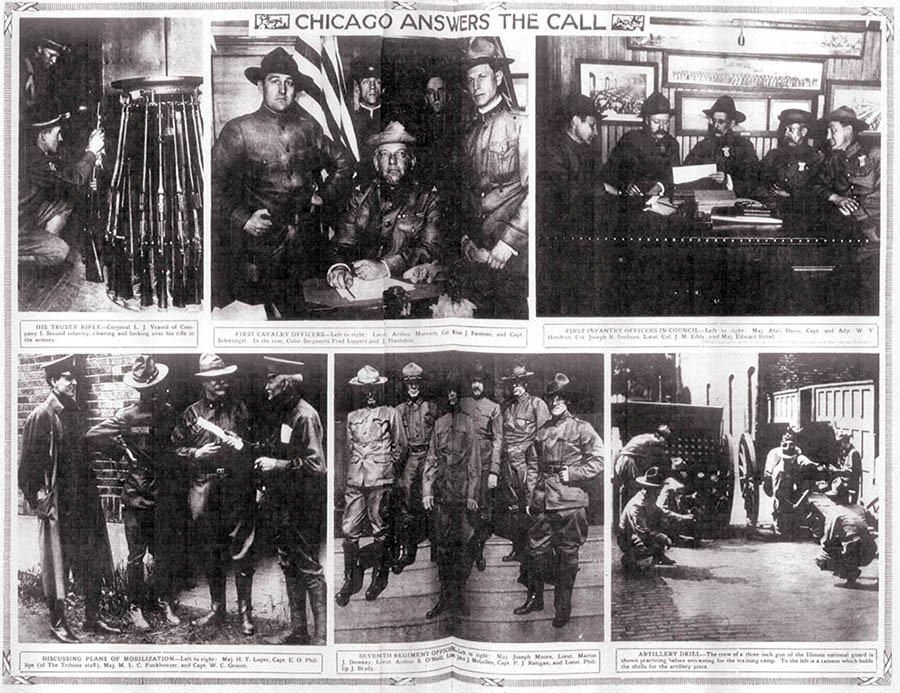

Chicago Daily Tribune, July 9, 1916 Col. Milton J. Foreman and the First Cavalry officers are pictured at top center.

|

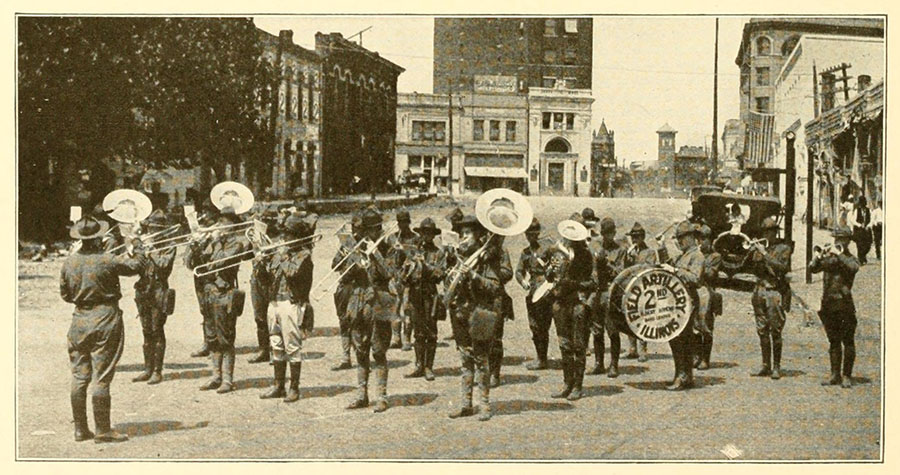

The 2nd Field Artillery band in Houston, Texas, in the summer of 1917.

|

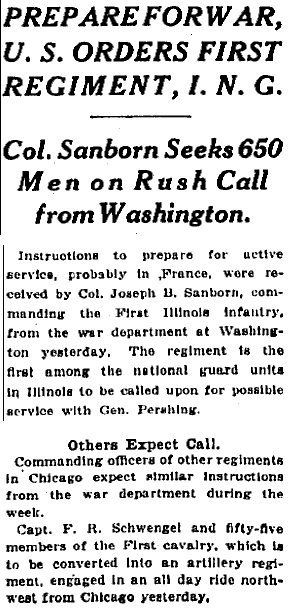

Chicago Daily Tribune, May 21, 1917

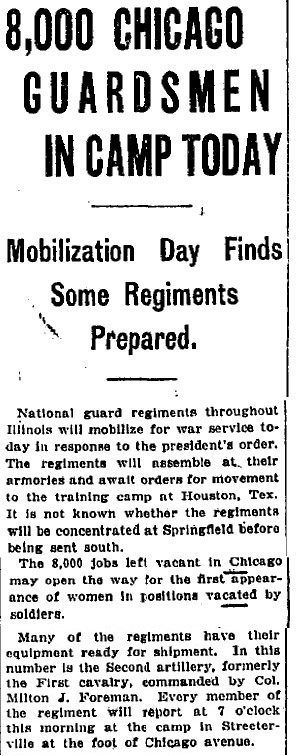

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 9, 1917

|

July 25, 1917

|

August 11, 1917

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, August 4, 1917

NEW ARMY GETS SALUTE TODAY BY ALL CHICAGO

City to Pay Parade Honor to Coming Fighting Men.

With the striking of 10 o’clock today the nation’s first parade in honor of the men who are called for service in the new national army will start at Michigan avenue and Eighth street and wind its way through the streets of the loop. Every man in Chicago and its suburbs whose name is in the first quota that has been called for probable military service has been invited by the people of the city to join in the event. The day is fitting. It is the third anniversary of the actual outbreak of the war, Aug. 4, 1914.

Lieut. John Philip Sousa and the band from the Great Lakes naval training station will occupy a position opposite the reviewing station at the Art Institute. Seven other bands belonging to military regiments in Chicago will take part in the parade.

Soldiers of the federalized regiments of the Illinois national guard will form in a line on the east side of Michigan avenue. The Second artillery will be stationed north of the reviewing stand. The Second, Seventh, and Eighth infantry regiments will be in line south of the reviewing stand.

Persons watching the parade from the sidewalks have been asked by the committee on arrangements to salute the flag by raising their hats and facing the colors.

|

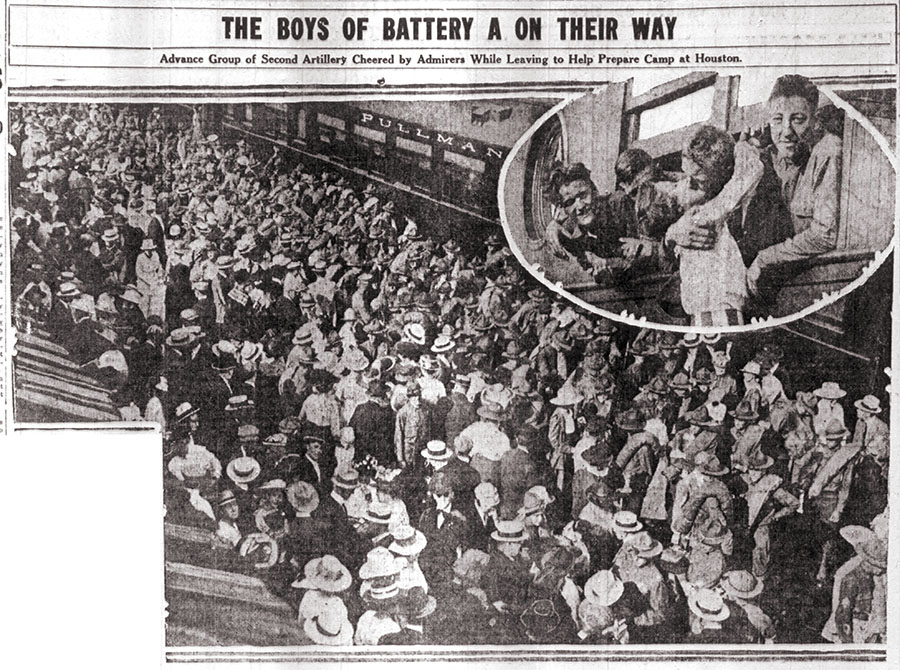

Chicago Daily Tribune, August 19, 1917

CHICAGOANS BID BRAVE GOOD-BY TO 2D ARTILLERY

2D FIELD ARTILLERY (Streeterville).

“Always leave them laughing when you say good-by.” It might just as well have been tears, but the assembled thousands fought hard with their feelings and made it a laugh instead.

It happened this way at the farewell to Col. Milton J. Foreman’s Second Field artillery last night in Grant park:

“Don’t stop till you carry the colors into the streets of Berlin; catch the Kaiser and then, boys, hurry back to us.”

Whereupon the band struck up: “We Won’t Be Home Until Morning!” The good-by ceremony was beautiful. Former Gov. Charles S. Deneen told them what they were going to France for. He told them what Chicago, what Illinois and what America expected of them, and what city, state and nation knew they would do: and with a suspicious moisture in his eyes in a voice that, trained speaker though he is, shook a bit, he bade them “good-by, good cheer, good luck – and Godspeed.”

Boul. Mich. Shaken by Cheers.

Boul Mich shook with the shrieking applause of the thousands upon thousands of Chicagoans who packed the park.

Mae G. Atkins sang “Your Flag and My Flag,” and they all joined in the chorus. Then the band struck up the opening bars of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The heavy boom of a gun smote the air, and the multitude bared heads and sang, while the cannon flashed and thundered the twenty-one salutes.

Then came the unique spectacle of a regiment, not escorting, but escorted by civilians. They walked the boys “home” – home to the camp at Streeterville. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, September 7, 1917

Foreman’s Men and Engineers First to Leave to Houston

The Second artillery has spent its last night in Streeterville until the Kaiser is licked.

Orders were received yesterday to continue the business of breaking up camp and loading equipment for the trip to the southern camp, and the time set for departure to Houston was late this afternoon.

For Col. Milton J. Foreman’s boys yesterday was a busy day, and last night was a busier night. In addition to getting the last of the equipment aboard train, there were farewells to be said to hundreds of mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, and sweethearts. This morning the only thing left on the camp ground was row after row of “pup” tents.

Guardsmen Shiver.

A raw east wind off the lake started shivering all the guardsmen without blankets, and all the visitors without summer furs. Early in the afternoon all the wall tents went down. The officers’ quarters were stripped clean, and they spent the night in a shelter building across Chicago avenue. The pup tents, with just room for two men, and blankets, formed the only protection for the enlisted men from the chilly wind and the hard ground.

The adjutant’s tent was the last to go down. When it had been loaded in the supply wagon a bonfire was kindled where it stood and men without work or visitors crowded about it.

Colonel on the Job.

Col. Foreman was very much on the job. Men who were with him on the border in 1916 says he is a stickler for leaving a camp stripped clean of trash. Attention to this detail and hurrying along the loading took him from one end of the camp to the other. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, August 17, 1917

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 11 1918

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, November 30, 1918

|

November 30, 1918 (article from headline, left)

[Special Cable to Chicago Tribune.]

Paris, Nov. 29. – It doesn’t seem likely the 122nd artillery from Chicago will be at any time part of the army of occupation. All the men are counting on getting back to Chicago soon. Part of their belief is based on the fact they already are well back of the old lines and are located at a rail head. They have turned their guns and horses over, seemingly only awaiting orders.

Enjoy Leave on Riviera.

Most of the officers have gone on their first leave in France and now are luxuriating on the Riviera. From the scores of men I have seen from the regiment there has been one name which has brought forth cheers of unsolicited praise, that of Lieut. Col. Schwengel, who only recently got his promotion.

The regiment has been several times cited in orders, both French and American. They have a splendid record, only losing fifteen men killed, while their wounded casualties are equally small.

Since the time they went into line they have fired off $900,000 worth of munitions.

Marshall Field a Captain.

Marshall Field received a captaincy a short time ago and was called to Gen. Bell’s headquarters. This young, modest chap, who never shirked at the hardest and most monotonous or unpleasant duty all the time from a simple private through to captaincy, is appreciated as much as any one in the regiment.

Although there is no official confirmation, it is the belief of the men that they will be among the first home. They are all so assured of it that they are laying heavy bets with all their neighboring regiments. |

| |

Chicago Daily Tribune, May 26, 1919

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 1, 1919

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 3, 1919

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 4, 1919

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 6, 1919

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 6, 1919

By Fred D. Pasley.

The men so tumultuously acclaimed yesterday will come back tomorrow civilians, secure in the knowledge that the stern promise implied in Pershing’s words at Lafayette’s tomb has been fulfilled through them and their fallen comrades. And their challenge will be, “Illinois, we are here.”

But yesterday . . . Say, did you see the parade? Or were you one of the perspiring thousands who squeezed and pushed and battered and elbowed and jammed and damned in a futile endeavor to penetrate the wall of hum backs extending along the Michigan avenue sidewalks from Twelfth to Randolph and then around the corner for the remainder of the line of the march?

The Parade’s the Thing.

The parade was the thing, the picture, the glorious emotional climax of the day. To be sure there were banquets after, and reunions in hotel lobbies and Grant park, and motor tours and parties, not to mention the demonstrations at the stations late in the afternoon when the units entrained for Camp Grant.

But it was the parade that provided the occasion for the mass enthusiasm – the spontaneous outburst of feelings pent up for an eternity of two years. The parade was scheduled to start from Twelfth and Michigan at 1 o’clock.

By 10:30 the people were banked sidewalk deep on either side and even an L guard could not have mortised in another human being. In the grandstands they were sandwiched in tier on tier. Some of them brought dinner baskets. All carried pennants with devices of the various units, and American flags.

Somewhere a clock struck 11. As if by magic all eyes, from Gov. Lowden down, were turned toward the Park Row station.

“They ought to be starting,” said Doc.

One of the Stay at Homes.

Perhaps you don’t know Doc. He is merely one of the vast legion of sty at homes, forced to accept the inexorable decree, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” He and his pals joined up in the old First cavalry the day after the United States entered the war.

When the regiment was federalized the regular army physicians disqualified him – impaired vision, defective kneecap, flat feet. Doc doffed his uniform and came back. Then he tried the marines, the navy, the Red Cross. Same experience. Next he went to the Salvation Army. He had signed up to go across purveying doughnuts when the armistice was signed.

And Here They Come!

“There they come!” a woman screamed.

Down the avenue a band was playing. Khaki clad figures could be seen debouching behind a platoon of mounted police from the Park Row station parking court. Away off in the distance there was handclapping. Faintly heard, at first, then it became louder as the crowds nearer took it up. Flags and pennants began to wave madly. A yell went up. Another and another.

The figures came abreast the governor’s stand. In the lead were Maj. Gen. George Bell Jr. and Brig. Gen. Henry T. Todd Jr. of the 58th artillery brigade. Gen. Bell left the parade for the governor’s stand leaving Gen. Todd to lead it.

“There’s Foreman and his outfit.”

Wowie! The grandstand had become a screeching bedlam. Women were dancing on the flimsy circus chairs. Flags were brandishing in uncomfortable proximity to one’s nose and eyes. The human wall along the avenue had become a gesticulating frenzied mob – stamping feet, waiving arms, yips and yells. One gentleman adjacent tossed his black derby in the street (maybe there was a method in his madness.”

Foreman Unmistakable.

It was Foreman, all right. No mistaking that swing of the bulking shoulders that snappy, resolute tread, the bulldog chin outthrusting from under the helmet tilted at a careless angle over the left eye. He wore no side arms, only in his right hand – habit of the cavalry days – was the inevitable riding crop.

“Hello, Milt,” yelled the gent bereft of the derby, and Foreman’s rotund, sunbaked features expanded into a broad grin.

One remembered that grin. It had characterized Foreman, the alderman; Foreman, the attorney; Foreman of the old First cavalry. It had been with him in his strenuous battles in municipal politics, whether he was on top of temporarily underneath – that grin.

Old Friends Appear.

“There’s old Slats,” yelled Doc. “Remember Slats, Cub reporter. One of the gang that used to hang around King’s. He’s regimental sergeant major. There’s Kent – Kent Hunter – captain of the headquarters. And look, Charley Biddle – the impressionistic artist – joined the day we declared war. Look at that guy. Corporal. Guess the old bunch didn’t make good, eh.”

But where are the others. In the band, for instance, Albert Bohene. You remember Al? He left the Chicago band to join up. Played the oboe. There’s one short. Al fell in the Meuse-Argonne that day when the Germans were laying down a heavy fire of shrapnel. He was hit. Died Oct. 12.

“O, you Red Breyn; Marie’s waiting for you,” booms a husky youth just in front of the grandstand and a stalwart artilleryman registers extreme self-consciousness.

A Gold Star Mother.

Battery A is passing. Observe the little woman with the black bonnet and the gold star on the left sleeve, who has arisen to wave her handkerchief from the top tier of the 122d auxiliary section. Her boy, Howard J. Wilhelm, was cannoneer with A until he was killed in action in the Argonne Sept. 27.

The regiment is passing in platoon front and there are many absent faces. In the auxiliary section you observe other women waving flags and handkerchiefs. Some wear gold start, others do not. But all the hands that wave greeting tremble somewhat. They didn’t tremble that way a few months ago when they were plying knitting needles – knitting in street cars, at theaters, everywhere – knitting socks and helmets and sweaters.

Girls Storm Lines.

On they come – Battery B, Batter C, D, E, and down the line – every man lithe of limb, steel muscled, bronzed, and clear of eye. And what’s this? The traffic policemen have been defied. They seem not to mind it. Girls, in summery white dressed, carrying huge baskets, have broken through the lines.

They skip alongside the marching column and tear the tissue covering from the baskets. They are filled with petals of roses, carnations, appleblossoms. They toss them in the air in great handfuls and the petals fall upon the rusty, dented, tin derbies. The tenants grin sheepishly.

Following the 122d came the 123d, commanded by Col. Charles G. Davis, and the 124th, commanded by Col. H.B. Hackett. They were warmly welcomed. They are composed of units from downstate and from Chicago suburbs. A large delegation had come in from Oak Park to greet Battery D of the 123d.

108th Engineers.

Just behind the 124th artillery there marched the 108th engineers, Col. Henry A. Allen’s regiment. Their history is linked with that of the Prairie division in all the major battles of the American phase of the war. They helped win the war by trigonometry. They were the men who precede the doughboys, laying pontoon bridges and railroads over swamps and rivers.

Bringing up the rear of the parade was Lieut. Col. George C. Amerson’s 108th sanitary train – 900 men, the majority of them from Chicago. They served with the British, the Australians, the French, and with the Yankee troops in the Argonne-Meuse.

Eleven killed and fifty-five wounded was their record. One of the wounded men marched yesterday. He limped and his left hand was in a sling. He was the only cripple to march in the parade. A dog trotted beside him. As he passed the reviewing stand a girl ran out and pinned a red rose on him. She was Blanch Cullinan of the Chicago Normal college.

Dog Wins Decoration.

“I can’t wear it,” he whispered,” but my dog can.”

The dog – a mongrel with a black body and white ears – wagged its tail as Miss Cullinan pinned the rose to his Sam Brown belt. The crowds cheered.

He wore it through the parade and even at the banquet at the Congress hotel.

Col. Foremen’s men were also banqueted at the Congress. The 108th engineers had their homecoming party at the Morrison.

And so Chicago welcomed home the last of her sons. For us the war is ended. But –

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row.

Lest we forget.

|

|