|

|

|

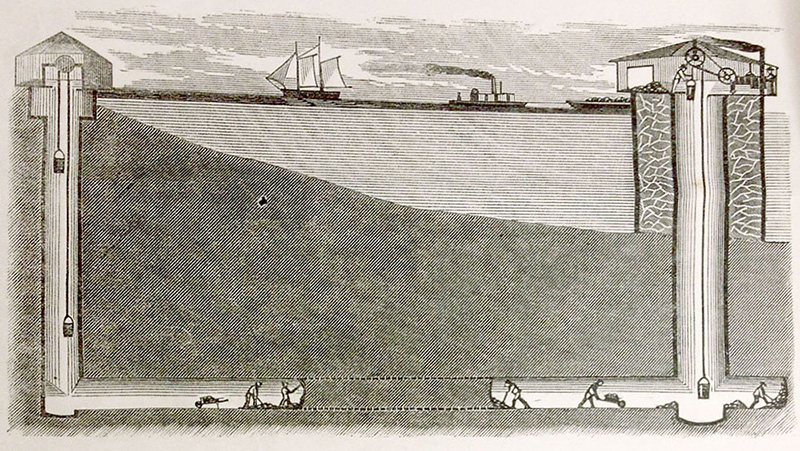

As detailed on this page within The Earlier Water Works sidebar, even with the massive Lake Michigan gleaming at its shore, the city struggled to obtain fresh water. Early on, there was a well north of the river, but otherwise people bought lake water from individuals who sold it by the container, and some utilized the river. In 1840, the privately held Chicago Hydraulic Company, began delivering water as a paid service, pumping water in through an iron pipe 150 feet out into the lake at the foot of Lake Street, and then feeding the water through hollowed logs to deliver it to subscribers. No fresh water was available north of the Chicago River until 1853 when the city's Chicago City Hydraulic Company reached further out into the lake and established its own pumping station at the foot of Chicago Avenue - at the same site where today's Pumping House now sits several hundred feet inland. Both companies dealt with the ongoing problem of fish clogging or being delivered through their pipes. During the time that the hydraulic companies pumped lake water from near distances into Lake Michigan, the city's population ballooned and industry waste polluted the river water. The south branch became known as bubbly creek from the slaughterhouse residue, while tanneries and distilleries created an indescribable effect in the north branch. (See the Carl Smith page.) From 1850 to 1860, Chicago's population more than tripled, growing from 30,000 to 100,000. In early 1862, engineer E.S. Chesbrough suggested that the city should reach a further distance away from the lakeshore and proposed extending a 5-foot tall flexable pipe two miles out, trenching into the lake bed. His proposal soon changed to one that suggested boring 30 feet into the lake bed then tunnelling to shore, meeting the 30-foot deep shaft dug by the pumping station. This became the Great Chicago Lake Tunnel. |

|

Illustration from the book, The Great Chicago Lake Tunnel, published in 1867. |